|

Global climate is probably the greatest long-term challenge facing the human race. Already our climate has changed and it will continue to change over the next century, with consequences for many aspects of the environment, society, and economy in all countries. The political profile of climate change and public awareness of its impacts have grown exponentially in the last few years. There is now consensus among the world’s leading experts within the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) that that every part of the globe will be affected by climate change, either positively or negatively. But the consequences will be potentially more significant for developing countries than for more prosperous nations: developing countries are the most exposed to extreme weather and disasters, the least able to recover losses caused by these events and the most dependent upon the environment for resources and economic development. While climate change may generate economic opportunities in some parts of the world, the adverse impacts of climate change are projected to outweigh its benefits, particularly in developing countries

Climate change [make footnote openable item] has the potential to exacerbate disaster risk (eg floods and droughts), food insecurity, health risks (eg increased disease vectors), natural resource depletion or alteration, gender inequalities, social and economic marginalisation – which can destabilise countries and lead to conflict and migration. It can also adversely affect transport networks and other infrastructure, and activities such as tourism. Sea-level rise and accelerated coastal erosion poses an existential threat to some populated areas as well as to critical infrastructure such as coastal oil rigs and power plants. Through these mechanisms, climate change can undermine or even reverse human development, posing serious challenges to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This is elaborated in the 2007/2008 Human Development Report, which focuses on climate change, and concludes that successful climate change adaptation coupled with stringent mitigation holds the key to human development prospects for the 21st Century and beyond. Ultimately, adaptation is an exercise in damage limitation and deals with the symptoms of a problem that can be cured only through mitigation. However, failure to deal with the symptoms will lead to large-scale human development losses (UNDP 2007). The OECD Declaration on Integrating Adaptation into Development Co-operation (2006) and the OECD Policy Guidance on Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into Development Co-operation (2009) detail the importance of integrating climate change considerations in national development frameworks and international aid efforts.

The latest and fourth report of IPCC, comprises three Working Group reports and a synthesis report released in November 2007 (available online at http://www.ipcc.ch/#). The latter is a powerful, scientifically authoritative document of high policy relevance. It addresses six key topics:

- Observed changes in climate and its effects.

- Causes of change.

- Climate change and its impacts in the near and long term under different scenarios.

- Adaptation and mitigation options and responses, and the inter-relationship with sustainable development, at global and regional levels.

- The long term perspective: scientific and socio-economic aspects relevant to adaptation and mitigation, consistent with the objectives and provisions of the Convention [sic], and in the context of sustainable development.

- Robust findings, key uncertainties.

It concludes that it is “at least 90% certain that human emissions of greenhouse gases rather than natural variations are warming the planet's surface” and makes several key projections:

- Probable temperature rise between 1.80C and 40C;

- Possible temperature rise between 1.10C and 6.40C;

- Sea level most likely to rise by 28-43cml

- Arctic summer sea ice disappears in second half of century

- Increase in heat waves very likely;

- Increase in tropical storm intensity likely.

Consideration of the impacts of climate change, and responses and adaptation to such change, must now be seen is a central element of addressing sustainable development in all situations. As a result, considerable attention is now being given to Climate Change Impact Appraisal (CCIA) with application both as an addition to traditional EIA and also as a part of policy-making and planning.

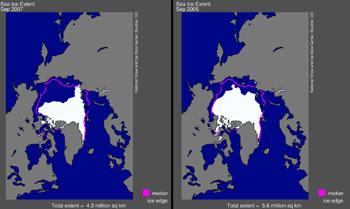

For example, The Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA) describes the ongoing climate change in the Arctic and its consequences: rising temperatures, loss of sea ice, unprecedented melting of the Greenland ice sheet, and many impacts on ecosystems, animals, and people. The ACIA is the first comprehensively researched, fully referenced, and independently reviewed evaluation of arctic climate change and its impacts for the region and for the world. The project was guided by the intergovernmental Arctic Council and the non-governmental International Arctic Science Committee. 300 scientists participated in the study over a span of three years. The ACIA Secretariat is located at the International Arctic Research Centre at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (www.iarc.uaf.edu). The 140-page synthesis report Impacts of a Warming Arctic was released in November 2004, and the scientific report later in 2005. Both can be freely downloaded from the ACIA web site (http://amap.no/acia/). Overall, the Arctic has warmed at twice the rate of the rest of the world. The seriousness of the situation was graphically underscored by satellite imagery taken in September 2007 which indicates that the arctic sea ice had melted to a far greater extent than had been expected or predicted (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1: Extent of arctic sea ice, September 2007

(Source: http://nsidc.org/news/press/2007_seaiceminimum/20071001_pressrelease.html)

This image compares the average sea ice extent for September 2007 to September 2005; the magenta line indicates the long-term median from 1979 to 2000. September 2007 sea ice extent was 4.28 million km2, compared to 5.57 million km2 in September 2005.

Internationally, UNEP has supported a country studies programme, focusing on capacity building in developing countries and economies in transition. Case studies were organized in Estonia, Antigua and Barbuda, Cameroon, Pakistan and Cuba. These served as a platform to test a UNEP Handbook on Methods for Climate Change Impact Assessment and Adaptation Strategies (Feenstra et al., 1998).

In the UK, the government and devolved administrations are actively examining how to address climate changes in a range of procedural requirements. Some instruments already require that climate change be addressed, eg the guidance for Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA is required for any form of regulation - formal legislation, Codes of Practice, information campaigns, etc.) which asks questions such as “Will the policy option lead to changes in emission of greenhouse gases; will it be vulnerable to the predicted effects of climate change?” (see: www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/regulation/ria/ria_guidance).

An OECD DAC Advisory Note on SEA and Adaptation to Climate Change [link to http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/0/43/42025733.pdf] describes how SEA approaches can help mainstream adaptation to climate change into strategic planning, in order to reduce the hazards, risks and vulnerabilities posed by climate change to systems and populations exposed to their manifestations and impacts (OECD 2008). [link to references] It argues that mainstreaming of climate change should lead to better informed, evidence-based policies, plans and development programmes that are more sustainable in the context of a changing climate, and more capable of delivering progress on human development.

Box 4.1: Useful sources on climate adaptation

Tools and data analysis relevant for addressing climate change considerations

[make links to websites]

-

IPCC Reports: Assessment reports that provide a comprehensive and objective synthesis of the latest scientific, technical and socio-economic findings relevant to the understanding of the risk of climate change globally. The website includes also IPCC special reports, methodology reports, technical papers and supporting material.

-

Knowledge Network on Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change Resource Center: This is the National Communications Support Programme’s (NCSP) library of literature, guidance documents, software packages and data sources for undertaking the various tasks involved in assessing climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation for the preparation of national communications by Non-annex I Parties to the UNFCCC.

-

ORCHID: Systematic climate risk management methodology which assesses the relevance of climate change and disaster risks to an organization’s portfolio of development project.

-

UNDP Adaptation Learning Mechanism: A project aimed at capturing and disseminating adaptation experiences and good practices via an open knowledge platform.

-

UNFCCC National Communications: Reports on the steps taken by the UNFCCC Parties to implement the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Included in these reports are national climate change vulnerability and adaptation assessments.

-

UNFCCC National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs): NAPAs identify Least Developed Countries’ (LDC) priority activities to respond to their urgent and immediate needs with regard to adaptation to climate change. The NAPAs are action-oriented, country-driven, flexible and based on national circumstances. The preparation of NAPAs was funded through the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), and implementation of identified LDC priorities is now underway based on priority project profiles, also through the LDCF.

-

UKCIP Adaptation Wizard: Open-source web-based tool designed to help the user to understand climate change and to integrate climate change into decision-making. It contains four steps consisting of impacts information, quantification of risks, decision support and planning, and an adaptation strategy review.

-

WE-ADAPT: An interactive space where users and experts share knowledge and experience on climate adaptation. Web space contains core themes on Framing Adaptation, Risk Monitoring, Decision Screening, and Communication, as well as tools and methods, worked examples and useful guidance to aid adaptation planning and implementation.

- Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO): Resources and information on the intersection of gender equality and climate change.

Guidance sources to support integration of climate change in planning and decision-making

Source: OECD DAC (2008) |

In developing countries, cities and municipalities are increasingly addressing how they will be affected by climate change, eg Durban (Box 4.2).

|

Box 4.2: Mainstreaming climate change into Durban’s Integrated Development Plan

The coastal city of Durban in South Africa is especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. It has recognised that the impacts of climate change are going to significantly affect the ability of eThekwini Municipality to deliver its sustainable development objectives and that climate change needs to be considered as a priority in the city’s planning. Therefore, the city initiated the development of a Municipal Climate Protection Programme (MCPP) in 2004 to understand the specific implications of climate change for the City and to put in place pro-active responses that ensure a sustainable city in the context of a changing global climate. The Municipal Climate Protection Programme (MCPP) is endorsed within Plan 1, Programme 6, of eThekwini’s Municipality’s Integrated Development Plan and has been developed in a phased manner:

-

Phase 1 focused on the assessment of the impacts of climate change on Durban. The Climatic Future for Durban (2006) documented these impacts and related development implications.

-

Phase 2: following on from the initial impact assessment, adaptation opportunities for key municipal sectors were explored through the development of a Headline Adaptation Strategy. This adaptation work is currently being extended and deepened through the development through a range of adaptation initiatives including the development of reforestation projects, community adaptation plans and the development of municipal adaptation plans for the water, health and disaster management sectors.

-

Phase 3: an Integrated Assessment Framework is being developed which will enable the simulation, evaluation and comparison of strategic development in the city in the context of climate change. This tool will allow decision makers to assess policies and plans in terms of projected climate change impacts and help educate the public about climate change and its implications.

- Phase 4: mainstreaming of climate change concerns into city planning and development. A number of opportunities have been utilized to mainstream the climate change issue, including: the creation of a Climate Protection Branch within the Municipality; establishing climate neutrality as a goal for the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup activities in Durban; the hosting of a Durban Climate Change Summit; and the launch of the Green Roof Pilot Project and the Buffelsdraai Community Reforestation Project.

Source: Dr. Debra Roberts (Environmental Planning and Climate Protection Department, eThekwini Municipality, Durban South Africa). |

|